What Elon Musk Gets Wrong About Ukraine

A brief history of Ukrainian electoral politics in the past decade

Greetings from Belgrade! A lot has happened since I last wrote. The tide has turned on the Kharkiv front. Putin has finally pushed the mobilzation button. Russia is in a state of panic as thousands of men flee conscription. The world now fears nuclear war more than ever as an increasingly desperate Putin locks himself further into a corner. The Crimean Bridge has taken extensive damage over the weekend.

As for me personally, I moved to Belgrade six weeks ago with my girlfriend. After securing a lease on an apartment, I went to the U.S. a few weeks ago for a mixed business and personal trip back home, before returning to Serbia last week.

Before I get into the meat of this newsletter, I want to express my grief on today’s missiles strikes in Kyiv and elsewhere. Throughout my time in the capital throughout the battle for Kyiv, I took a measure of comfort in walking through the city center even as the sounds of combat loomed in the distance. The city still felt safe somehow on a visceral level, as if Kyiv was an old friend that was looking out for me. The images from today have therefore been especially painful.

I am writing today about Elon Musk’s recent (re)-entry into the war discourse. While hopefully the matter will remain relatively trivial, his deeply misinformed points provide a great opportunity to refute some of the most commonly-held misconceptions about Ukrainian unity. Today’s newsletter will mostly be Ukrainian Politics 101 material, so more knowledgeable observers can probably skip this one.

Musk first waded into the discourse on October 3 with a four-point peace plan on terms favorable to Russia. It was understandably a great source of disappointment for Ukrainians, who had considered Musk their friend after he gave them access to Starlink in the early days of the invasion. Having once used a Starlink-based wifi network to contact my girlfriend from a base near the frontline in Sviatohirsk, I can personally attest to its usefulness. Although, somewhat ominously, Ukrainian forces have reported failures last week.

Musk’s proposal read like that of an armchair policy wonk who has passively internalized Russia’s narrative. The Kremlin, of course, will not consent to any “redo” of the faux-referenda on genuinely democratic terms, rendering the idea moot and stupid. Nor is neutrality a feasible position for Ukraine; they tried that from 1991-2014 with bad results. As for the notion that Crimea has been rightfully Russian since 1783, he is using the same logic that justifies Russian chauvinists’ claims to most of Ukraine. Kyiv, after all, had been effectively folded into the Tsardom of Muscovy more than a century earlier.

President Zelensky, in his usual showman fashion, replied with a Twitter poll of his own.

U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham also chimed in with a polite rebuttal against Musk’s tweet, prompting a reply from the Tesla CEO that betrayed a common but fundamental misunderstanding of the war. Given the seriousness and ubiquity of the error, it deserves thorough refutation.

The gist of the argument is that Ukraine is essentially two countries squeezed into one, with a pro-Russian east and anti-Russian west. Samual Huntington described it in terms of a civilizational battleground between the Catholic and Orthodox worlds. He was terribly mistaken; in fact, only three of Ukraine’s 24 oblasts have a Catholic majority. Even among Ukraine’s Catholic population, the majority are Eastern Catholics (also known as Greek Catholics). Without digressing too much into theology, these Catholics follow the same liturgy as Eastern Orthodox Christians. The crucial difference is that, for reasons that varied across time and place, such churches reestablished full communion with the Vatican following the Great Schism in 1054.

Since the beginning of the war in 2014 (Huntington died six year prior), electoral politics has replaced religion as the cornerstone of the argument that Ukraine is a split nation. They invariably use maps from before the 2014 election, highlighting the former success of the Russia-friendly Party of Regions in eastern and southern Ukraine.

It is true that the Party of Regions, which dissolved following the overthrow of its President Victor Yanukovych in the Maidan revolution in February 2014, was broadly “pro-Russia” in the sense that it favored friendly ties. It is absolutely true that many of the Kremlin’s local proxies in the occupied territories have roots in that party. But is it correct to infer that its former political strongholds wish to be part of Russia? Absolutely not.

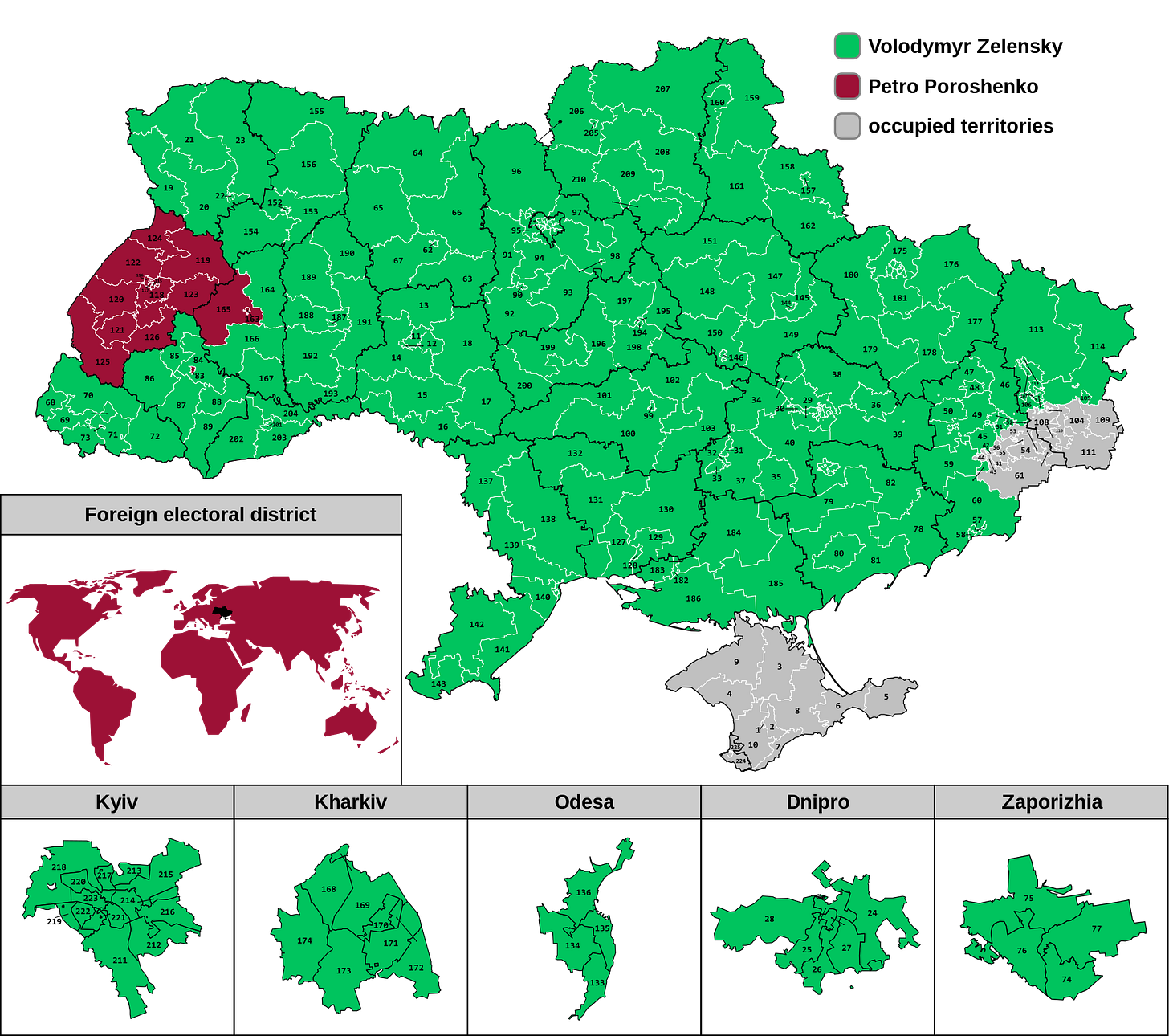

Many things get lost by people like Musk when they circulate these maps. The most obvious flaw is that a lot has changed in the post-Maidan political landscape. Below are the results of the first round of voting in the 2019 election.

As you can see, Zelensky cleaned up the map in most places that were previously the domain of the Party of Regions, including every district in what is now occupied Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. Yuriy Boyko, whose Opposition Platform-For Life party was one of the spiritual successors to the Party of Regions, was only able to hold onto the Donbas, a pair of districts in Ukraine’s portion of Bessarabia and a single district in Kharkiv Oblast. Despite the holdouts, Zelensky had already broken the usual electoral map of 21st Century Ukraine.

In the second round of voting, Zelensky won all the districts that had initially gone for Boyko. Only Lviv Oblast in western Ukraine voted for the incumbent, Petro Poroshenko, along with two districts in neighboring Ternopil Oblast. Everywhere else, including the country’s westernmost and easternmost districts, went for Zelensky.

Now that we have seen how drastically Ukrainian politics has changed in the past decade, let us go back to the parliamentary electoral map from 2012 posted by Musk. A comparison of all the aforementioned maps gives the impression that something drastically changed between 2012 and 2019, and that is certainly true. But it is not the full story.

Referring to the Party of Regions as “pro-Russia” works as a short-hand term. Its ousted President Yanukovych, whom Putin had originally cultivated to win in the 2004 election, fled to Russia in the wake of a revolution inspired by his subservience to the Kremlin. And he certainly appeared staunchly pro-Russia on the campaign trail when compared to his predecessor, President Viktor Yushchenko.

What gets forgotten, however, is that EU integration was a centerpiece of the Yanukovych government. His presidency’s foreign policy, until the last minute, could best be described as wanting warm ties with Russia, good relations with the West and neutrality in military affairs. For all his links with Putin, it was the Yanukovych government that spent years painstakingly negotiating the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. His ties to the Kremlin were certainly known – he was, after all, the loser in the 2004 Orange Revolution – but by the 2010 election he had reinvented himself (with the help of Paul Manafort) as an advocate of moving Ukraine closer to the rest of Europe. For most of his presidency, Yanukovych appeared to be working to keep that campaign promise.

When Yanukovych suddenly reneged on signing the association agreement in November 2013 after an unexpected trip to Moscow (he had also met Putin on two other occasions in October), it was obvious what had happened. Through a combination of coercion and enticement, Putin was ordering Yanukovych to trash what would have been his foreign policy legacy mere weeks before it was to be signed. Yanukovych was not acting at the behest of his constituents; even the “pro-Russia” ones were under the impression that warm ties with Moscow were not mutually exclusive with autonomy in foreign affairs. Putin thought otherwise, thus Yanukovych made a major policy u-turn simply because the Russian president ordered him to do so. It was at this moment that the cracks in the Ukrainian social contract reached its breaking point, resulting in what is known in Ukraine as the Revolution of Dignity.

Not all Ukrainians, of course, were particularly thrilled with Yanukovych’s ouster. Had Putin allowed the political dust to settle instead of sending in the military, Ukraine would have likely kept its course of alternating between governments that slanted westward in some election cycles and toward Russia in others. Instead, Ukraine got a Russian invasion in the Donbas and the annexation of Crimea. Much of the Russia-leaning populace was amputated outright from the electoral maps, while others began reconsidering their options in a process that continues to this day at an especially accelerated pace.

Ukraine remains a socially diverse country, with regional political differences similar to any nation of its size. It is not split down the middle between “ethnic Ukrainians” wishing to remain independent and “ethnic Russians” wishing to be reunited with the motherland. Even those with pro-Moscow leanings, by and large, have seen their love of Russia shaken to the core in recent months.

Take this guy, Mykhailo Dobkin, for instance.

For the past decade, this former governor of Kharkiv and ex-mayor of the city of the same name has been about as pro-Russia as one gets in Ukrainian politics. At the time of the Euromaidan revolution, he was calling for protesters to be killed. These days, he dons the uniform of the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

While I am in no position to say whether his change of heart is genuine, I have no doubt that he is responding to a genuine conversion among his constituents. As I reported in May, I spoke to Kharkiv Oblast residents who expressed disillusionment with the Russian nation. “I used to love Russia so much,” said an elderly woman, who had approached me unsolicited on the streets of the ruined town of Slatyne near the Russian border, with tears in her eyes.

How, exactly this war will impact Ukraine’s next election remains to be seen. We are not even sure where the boundaries of effective state control will lie. But it will certainly be a new chapter for the nation’s politics, and thus far the country’s response to the full-scale invasion has been a success story for inclusive civic nationalism, with freely-expressed speech evaluated for its content rather than in which language it is spoken. Regardless of what happens next, it is unlikely to have much to do with the election maps of the last decade.

Liked the post, I have been making similar arguments! The difference between pro-Russian sentiment and secession is shown in International Republican Institute and Pew polls of 2014, both made after the Maidan revolution. In the east, a majority wanted to join the Russian customs union, have Russian as a joint official language and have a positive attitude towards Russia. However, allowing regions to secede from Ukraine polled 18% in the east.

I disagree with the idea that you can infer a shift in public opinion based on Zelensky's support in the election. He campaigned for negotiations with the Russian government, presumably this means allowing for some autonomy in Donbas. A slight majority wants to either succeed or become an autonomous republican inside a Ukrainian state, according to research by Ivan Katchanovski.

How would you go about learning about preferences and voting behaviour in Ukraine today? Many KIIS polls on separatism appear to be sampling on the dependent variable by not surveying separatist or Russian-controlled areas. Further, does the threat of violence from both sides make honest answers hard to obtain?

https://www.iri.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/iri.org/2014%20April%205%20IRI%20Public%20Opinion%20Survey%20of%20Ukraine,%20March%2014-26,%202014.pdf

https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2014/05/08/chapter-1-ukraine-desire-for-unity-amid-worries-about-political-leadership-ethnic-conflict/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23745118.2016.1154131?journalCode=rpep21

A useful essay. I hadn't seen the 2019 first round map before. It shows, though, that the Donbass *was* opposition territory. That's not Zap-Cher, but it's important.

My own thoughts are at:

https://ericrasmusen.substack.com/p/good-and-bad-reasons-why-the-united

I support Ukrainia, but for other reasons.